Why do native oysters need protecting?

Native oyster reefs were once abundant in European seas but sadly it is estimated that populations have declined by 95% since the 19th century. Now native oyster reefs are now one of the most threatened habitats in Europe.

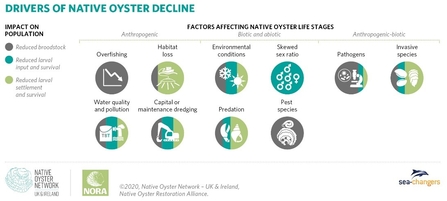

The key driver behind this huge decline is historic overfishing, however, habitat loss, disease, pollution and invasive non-native species are all contributors. Native oysters are also characterised by a slow growth rate and sporadic recruitment, which further limits their success.

In Northern Ireland, extensive oyster beds are known to have existed in Carlingford Lough, Lough Foyle and Belfast Lough for several hundred years, but most stocks crashed during the late 19th or early 20th century. Now only a small wild population exists in Strangford Lough.

Conservation Status

The native oyster is a Priority Species in the UK and Northern Ireland. A Priority Species requires conservation action because of their decline, rarity and importance in an all-Ireland and UK context. It is included in the OSPAR List of Threatened and/or Declining Species and Habitats for the North-East Atlantic.

How is Ulster Wildlife helping?

According to the Irish Fisheries Commissioner, all native oyster fisheries in Ireland had collapsed by 1903 due to overfishing, pollution and the spread of disease.

However, in the summer of 2020, live native oysters were discovered for the first time in over 100 years in Belfast Lough– evidence that the environmental conditions for re-establishment were right. To support the natural recovery of the native oyster, Ulster Wildlife installed Northern Ireland's first native oyster nursery in Bangor Marina, in April 2022, funded by the DAERA Environmental Challenge Fund. Similar projects have been established in other parts of the UK.

A year later and our second native oyster nursery has been installed at Glenarm Marina. The native oyster was once common in and around Glenarm – remnants of old oyster shells can be found along the Glenarm coastline and even seen from the pontoons in the marina.

An oyster nursery is a micro-habitat housing mature oysters that will reproduce and release the next generation of oyster larvae to settle out on the seabed. An individual oyster can release up to 1 million larvae per year! The cages are hung in the water underneath the pontoons, which protects the oysters from predation.

With funding from DAERA through the Environment Fund, supported by a generous donation from Wilson Resources Ltd, we will be expanding the number of native oyster nurseries in Northern Ireland over the next five years.

Native oyster nursery at Bangor Marina - the first initiative of its kind on the island of Ireland

Restoring native oysters to Belfast Lough (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PIFfdCctyIs)

Find out more about our ambitious restoration project to help bring back native oysters to Belfast Lough by establishing the first native oyster nursery on the island of Ireland.

How can I help native oysters?

Choose sustainable seafood options

Many of the oysters on sale and eaten in the UK and Ireland today are pacific oysters. This is an invasive species, and was brought here intentionally from Japan in the 1970’s following the demise of our native oysters. Many farmed pacific oysters are "triploid" - meaning they are sterile and won't impact on wild populations. It's not entirely failsafe - but they are a more sustainable option. For more information on making good seafood choices, check out our Sustainable Fish City campaign

FAQ's

Why restore native oyster reefs?

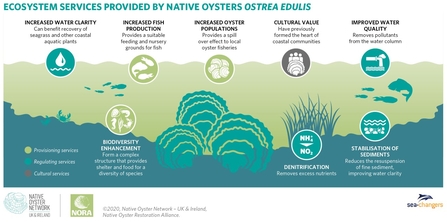

When oyster reefs are restored, their ecosystem services and function are restored, which help keep our ocean healthy and resilient. A single oyster can filter up to 200 litres of seawater (approximately a bathtub) per day, which can significantly improve water quality and clarity. By removing particles from the water column, the oyster can also increase light penetration to the sediment and promote the recovery of seagrasses, another threatened and valuable coastal habitat. Left undisturbed, oysters will form reefs providing habitat for lots of other species, including important commercial fish.

Ecosystem services provided by oysters (c) Native Oyster Network

Can oysters store carbon?

The drawdown of sediments together with the stabilising effect of the reef can result in reefs acting as carbon sinks although the ecosystem benefit is complicated (read more here). However, existing oyster reefs can protect considerable stores of carbon that should be protected to avoid further releases of carbon into the atmosphere. Carbon sequestered and stored in the marine environment is called blue carbon.